Previously published on EdSurge.

Who are you?

If you saw this question on a government form, you’d likely respond in a practical fashion, checking boxes about how the world perceives you. Where were you born? What’s your family’s income? What’s your race? Did your parents—even your grandparents—graduate from college?

They’re answers that, when it comes to education and work and success, aren’t supposed to matter—but seem to anyway.

Who are you?

If you saw this question at the top of a page in your diary, though, you might take a different approach, scribbling details about how you perceive yourself. What do you love to do? What scares you? Who matters most to you?

They’re answers that, when it comes to education and work and success, don’t always seem to matter—but maybe should.

Among American adolescents, that “official” information—about their family histories and resources—varies immensely. But when it comes to their inner lives, they tend to have a lot in common. They don’t all have money, or connections, or other advantages. But they all have dreams.

Yet not everyone’s aspirations count the same in shaping their lives. Some students—often wealthy students—grow up assured that they can and should follow their dreams. Others grow up in environments that, explicitly or implicitly, treat their dreams like a luxury—nice to have, but hard to afford.

This disparity plays out as teenagers make decisions about what to do after high school. And it’s complicated by common wisdom that advises young people that the path to dreams almost always passes through college—even though only some students make it there, and even fewer graduate.

This forces many teenagers to grapple with contradictions: College is essential, but it’s also impossible. It pays off, but it’s also too expensive. It’s for everyone … but maybe not for you.

Seeing these incongruities, more employers, politicians and even educators are encouraging alternative routes to adulthood—often specifically to employment. If campuses and classrooms seem beyond reach, these grown-ups advise, seek opportunities elsewhere. Train to gain skills that are practical, marketable. Securing a steady job and a solid paycheck doesn’t require college.

That message may be true. Yet it’s advice typically reserved for only some young people—and it may fail to resonate with them. Even teenagers whose circumstances constrain them tend to lean into their potential, not their limits. So many of them want more than a job. They want good lives. They want to grow and thrive. They want opportunities that inspire them.

To create those opportunities, adults may need to start listening. Colleges and companies, philanthropies and governments are busy redesigning postsecondary pathways, trying to reduce—or prevent—student loan debt, to make training options more flexible, and to prepare more workers for jobs in growing industries. What would happen if leaders paused these efforts to ask teenagers new kinds of questions, and really heard what they have to say?

In Tennessee, Dino Sabic longs for a way out of pandemic stress. In Texas, Maytee Guadiana worries about not being able to complete her degree. In Louisiana, Vernell Cheneau III hopes to be his own boss.

On the cusp of graduating from high school in spring 2021, these three teenagers, plus six others, shared their thoughts and feelings about the lives they’re working toward and the choices they’re making to get there. Their reflections captured at that moment, along with insight from more than two dozen counselors, economists, psychologists, employers and workforce experts, offer a glimpse at how postsecondary pathways could serve young people better if recreated for their adolescent brains and crafted around their dreams.

“We should not be designing programs and interventions without the direct input of young people,” says Allison Gerber, director of employment, education and training at the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a philanthropy based in Baltimore that makes grants to expand education and skills-training for youth and adults. “The more engagement and ownership young people have in the entire thing, the more likely it will meet their needs, they’ll want to stay, feel a sense of belonging, and it will be attractive to them and their peers.”

We might start that design process by asking each young person who they are, about their goals and values, and how they envision their futures. That conversation might begin with students’ hopes and fears.

On this journey you will learn:

I. How ‘the education system and the economy are in cahoots.’

II. Why, when it comes to adolescents, ‘the passion piece is so important, as opposed to the paycheck piece.’

III. That teenagers have stumbled en route to adulthood because ‘there were so many barriers in the way.’

IV. Why some adults believe ‘it’s on us to open that window’ to good opportunities for young people.

Along the way, you’ll meet teenagers:

dealing with STRESS, seeking INDEPENDENCE, searching for job SATISFACTION, engaging in EXPLORATION, honing their LEADERSHIP skills, dreaming of HELPING OTHERS, worrying about MAKING MISTAKES, craving STABILITY, and AIMING HIGHER to make their families proud ?

FEAR: Stress

To earn some cash—and the freedom that comes with it—Dino Sabic got his first job, at a Food City, when he turned 17. He found perks to working at the grocery store, where his mother is the manager. It was close to home. He enjoyed chatting with customers. He liked managing money.

But managing his time, Dino says, became “a big, big struggle for me.” When school ended at 2:15 p.m., he practiced with the football team until 5 p.m., and then worked at the store from 6 p.m. to 11 p.m.

“It was a nice little job at first,” Dino says. “It just got too taxing on, I guess, my mental health and how much work I got done in school.”

Dino says he never used to get stressed out—even though his early memories include seeing bullet holes in buildings. He was born in Bosnia-Herzegovina after the Bosnian War. The conflict “kind of tore everything apart,” Dino says. It forced his mother and grandmother to run for miles as refugees seeking shelter. It turned his stepfather into a soldier at age 17.

When Dino was younger, his mother left a good job in Bosnia to move with him to Tennessee. She wanted to reunite with her husband, who had moved to Chattanooga after the war. She also wanted, Dino says, “to give me the best opportunity to shape my life.”

Dino celebrated his seventh birthday on the airplane ride to America. He started school there without knowing any English. Yet he says it was working toward high school graduation during the coronavirus pandemic that really strained him.

“I was never one to get sad over things, but it’s just when everything is just thrown on your plate, and on and on and on—and you’re not really in school, you’re out of school at one point—and just things are constantly changing, you can never settle. That’s what stresses me out. Just constant, constant, constant change,” Dino says. “It doesn’t bother me as much as it did, but this year definitely had a huge, huge impact. COVID as well, really.”

Dino had always wanted to go into health care, to help people like his little brother, who has a mitochondrial disease that stunts growth. But now Dino wonders if studying medicine requires too much work, or if medical school is too expensive.

“I hope the next four years aren’t really too stressful on me,” he says. “I plan to work a lot. I plan to study a lot. I just plan to push myself and just achieve goals throughout college. But I also plan for it to not be as stressful as people make it seem.”

To figure out how to approach college, Dino seeks advice from adults in his life, asking what they studied and where that led them. His football coach talked him through the pros and cons of the careers that interest him.

Dino now works on the weekends for a logistics firm, where he says his boss “kinda grew up from nothing as well, and he made it big with this company.” So Dino is considering studying business in college, keeping in mind what some of his teachers used to say during meetings with his mother.

“They said, ‘Dino’s a great kid. He is going to make it big. You can really tell that he’s going to be his own boss,’” he says. “And I just want to make it big.”

But to Dino, that doesn’t mean affording a flashy lifestyle. It means being “financially set and emotionally set”—stable enough “to be there for people.”

“People in my life have been so supportive, and they have made it known that they’re always there for me,” Dino says. “And I just want to do the same thing back.”

HOPE: Independence

Vernell Cheneau III takes his cues from media. He watches TV shows like “Shark Tank” and “The Profit.” He’s a fan of Graham Stephan, a personal finance YouTuber who sells real estate.

“This is the consensus I came to in the tenth grade,” Vernell explains. “There’s one thing in this country that matters, honestly, and it is how much money you can get before you die.”

A native of New Orleans, the high school senior giggles when he talks. He likes Star Wars and Magic: The Gathering. He breaks into goofy voices when he tells stories.

But he’s serious about money. He checks his credit score. He’s interested in stocks and cryptocurrency. He recorded a podcast about universal basic income.

“I am a strong, determined Black male,” Vernell says. “I feel like that’s as clear, cut and dry as it gets.”

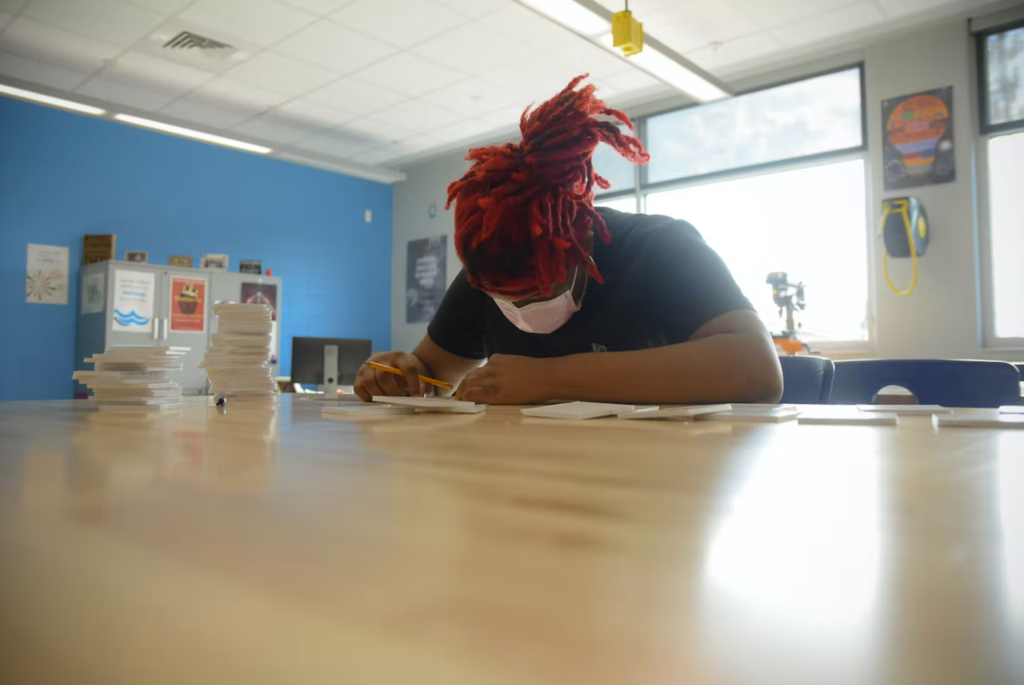

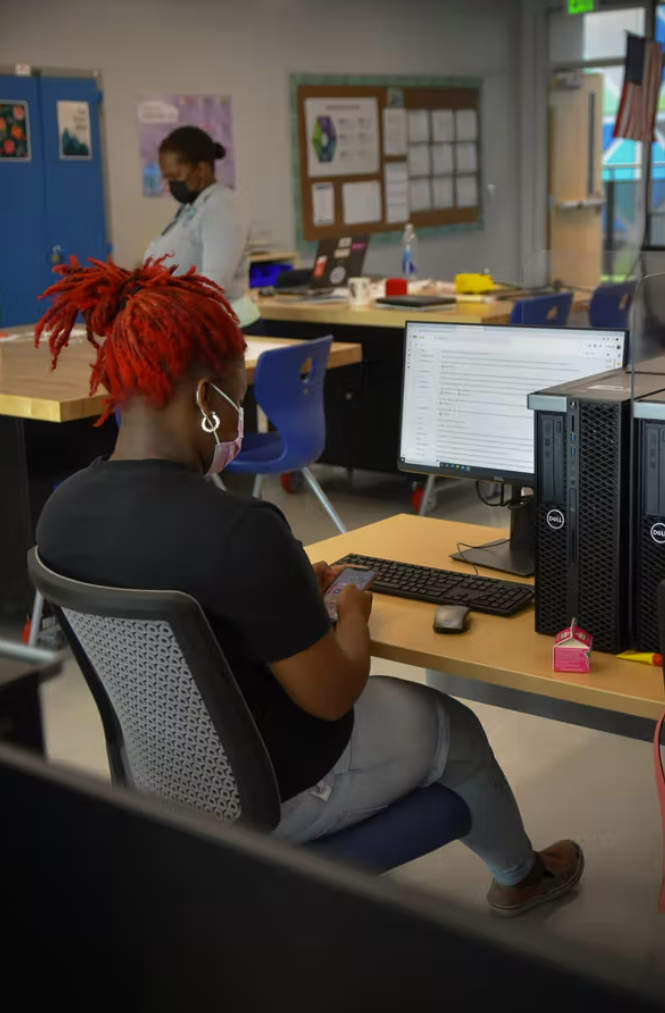

Vernell tries to make the most of his time. Throughout the day, he does self-paced, online schoolwork, edits audio and video for a paid digital-media-production internship, and resells sneakers and phone cases through online marketplaces—which means he sometimes needs a ride from his mom to mail deliveries at the post office.

“I work like a train,” he says. “If I keep chugging along, I’m going to keep going. But if I stop, then eventually I’m going to come to a creaking halt.”

People can’t tell me what they’re going to college for. But they put themselves in thousands and thousands and thousands of dollars of debt.

—Vernell Cheneau III

Vernell’s mom keeps busy, too. She “makes all of her money on side hustles,” he says, like delivering for DoorDash and Shipt. Vernell’s father is incarcerated. Some of his other family members work at Walmart. The relatives he considers most successful in their careers are an aunt who works as a nurse and an uncle who owns and drives a truck.

“There’s not really many people in my family who went to college,” Vernell says. “And if they did go to college, they didn’t stay in college and then do what they went to college for, which is part of the reason why I personally told myself that I didn’t want to go to college.”

He’s given that a lot of thought. He doesn’t buy into the idea that college is some kind of coming-of-age experience worth paying for.

“This is a school, an institution that I am paying money for—an investment,” Vernell says. “Do I think that the knowledge that these people will teach me is going to be worth it in the end? I did the calculations to myself. Wasn’t worth it in the end.”

When he asks folks why they want to go to college, he’s not impressed with what he hears.

“People can’t tell me what they’re going to college for. But they put themselves in thousands and thousands and thousands of dollars of debt—that doesn’t sound like it makes any sense,” he says. “That’s like buying a car and not knowing how to drive.”

Besides, Vernell has an alternative lined up. Days before graduating, he landed a job in the human-resources department of Entergy, a Fortune 500 energy company. The opportunity came through a workforce fellowship Vernell completed in high school, where he also earned certifications in Autodesk Inventor design software, email marketing and inbound sales.

He’s excited about the $17-an-hour pay—and the fact that he thinks he’s one of the only people ever hired at Entergy right out of high school.

“That’s big, especially for me, you know, knowing what I can do with that money and that experience and those connections,” he says. “Things of that nature are just invaluable.”

Vernell sees it as a next step toward becoming an entrepreneur. He wants to own a cannabis company. When that industry takes off, he says, “it’s going to the moon.”

The goal is part of the ethic Vernell’s mother instilled in him, he explains, “to be a boss.” Don’t be a chef—own a restaurant. Don’t be a doctor—own a hospital.

“So now, I have that ‘I have to have my own’ mentality,” he says.

Vernell is pretty sure his family thinks of him as “an anomaly.” But he knows they are proud of him.

“When I tell my mom all the things that I’m doing, she doesn’t know what I’m talking about,” Vernell says, “but she loves the fact that she doesn’t know what I’m talking about.”

I. ‘The education system and the economy are in cahoots’

Adorned in a gown, diploma in hand, each student crossing the high school commencement stage has some power to decide what to do next. Yet the options readily available to them differ, influenced by forces far beyond their control.

It’s those forces that Anthony Carnevale studies. He’s an economist who has become an expert on higher education.

“Economists are now in the game because the education system and the economy are in cahoots,” says Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

That link means a teenager’s education decisions are also economic choices, ones with the potential to powerfully shape the rest of a young person’s life. The stakes are high—higher than many 18-year-olds realize.

That’s partly because the game has changed, and not all families have caught up or caught on. What Carnevale views as the modern era of higher education is not even 40 years old—younger than the parents of many of today’s teenagers. The economist pegs the start of this new age to 1983. That’s the year when the financial payoff of college started to shift. Before that, workers who had a college or graduate degree made about 40 to 50 percent more money annually than their peers who had only high school training. After that, the financial benefit of a college degree grew rapidly, so that by the early 2000s, workers who earned advanced degrees made about 80 percent more annually than their peers who only finished high school.

A teenager’s education decisions are also economic choices—and the stakes are high.

Today, only about 20 percent of people who just have a high school diploma can get what Carnevale calls a “good job”—one that pays at least $35,000 for workers younger than age 45 and at least $45,000 for workers ages 45 to 64.

It’s pretty clear that most people would benefit in life-changing ways from learning or training beyond 12th grade. It’s less obvious what form that study should take, and whether the solution is the same for everyone.

There’s a debate underway about what paths are best for young people. It tends to frame the question as a choice between higher education or job training, assuming those are divergent pathways serving distinct purposes and populations. And when the chief debaters—adults—argue about this topic, they tend to focus intently on one consideration in particular: money.

Over the past four decades, the cost of going to college has soared. Meanwhile, the job market for youth has “collapsed,” Carnevale says. So even as college became more important as a ticket to well-paying work, the ticket price for a degree rose, and it became less possible for young people to pay for tuition by working their way through school. Because of all that, the age at which young people reach “economic independence”—that is, when a majority of them attain a good job—has increased since the 1980s from the mid-20s to the early 30s.

Escalating tuition expenses, overwhelming student loan debt, teenagers working two jobs to help support their parents and siblings—all this has led to shifting rhetoric about what students should do after high school. Politicians and corporate leaders cite these problems with concern—sometimes, no doubt, to serve their own agendas. And so the “college for all” enthusiasm of the Obama era gave way to a “skills not degrees” ethos of the Trump years. Employers hungry for workers and a more racially diverse workforce started championing “skills training” offered by apprenticeships and certificate programs rather than the liberal arts coursework traditionally prized in higher education.

The expense of earning a college degree has made that pathway too narrow for many people to travel, says Kelli Jordan, a human resources executive at technology company IBM. “Thinking about the skills—versus that piece of paper or that credential—helps to open up the aperture” for hiring, she explains.

Even educators are changing their expectations. Public schools in cities and rural regions are adopting curricula focused on job skills. In places where college completion rates are low, like Baltimore and New Orleans, some teachers and counselors say they now encourage high school students to consider local job-training programs instead of only pointing them toward college.

“Students I’m working with can move up in the world with education, but I also understand that if they can’t, they can’t,” says Andrea Moreno, who advises high school students in San Antonio. “If I already know they can’t afford it, I’m not going to push it.”

Big believers in the value of a college education must contend with the troublesome truth that some degree programs lead to better job outcomes than others. And more years of study doesn’t always equal more pay. For example, about a third of (two-year) associate degrees lead to jobs that pay off better than the average (four-year) bachelor’s degree, according to Carnevale.

“We live in a world where, if you’re thinking strictly in purely mercenary, economic terms, there are a lot of one-year certificates that outperform bachelor’s degrees—ventilation and air conditioning” for example, he says.

So not every worker needs a bachelor’s degree to make a decent wage, and not every bachelor’s degree benefits every worker. There are strong employment opportunities in health care, the skilled trades and the technology and energy sectors, sometimes called “middle-skill” or “new-collar” jobs, that don’t require a four-year credential like a B.A. (Bachelor of Arts) or B.S. (Bachelor of Science).

But, Carnevale says—and it’s a big but—“the B.A. is still, long term, the degree for the advantage. It gives you more adaptability.”

Who deserves the advantage of a college degree?

Who deserves that advantage? It’s an uncomfortable question, one that’s rarely asked aloud but is no less real for remaining unspoken. And the people with the power to help decide—from the White House to the board room to the principal’s office—aren’t always impartial.

When governors and state workforce-policy leaders consider middle-skill jobs, Carnevale says, “there’s a tendency to see them as ‘good enough’ for Latinos, African Americans and working-class whites.”

That means, he adds, that “if you’re white and upper-middle-class, you’re going to get a B.A. If you’re working-class white, and/or minority, you’re going to be tracked into training. And this can be a feel-bad experience for a lot of people.”

It doesn’t feel good when experts far beyond your reach decide what’s best without ever consulting you. Yet that’s how new postsecondary paths for young people are being laid and paved. Meanwhile, teenagers trying to make deeply personal decisions about where to go stand at the edge of a shifting landscape without so much as a map.

“Do we have an apparatus that in any way helps people negotiate or find their way in this whole new world? The answer is no, we do not,” Carnevale says. “Much of the infrastructure necessary for that, when you’re thinking about college and careers, simply doesn’t exist.”

But as much as teenagers trying to find their way need better navigation tools, adults constructing new highways need better insight about where young travelers want to end up. And even an economist says that kind of information doesn’t spring from a spreadsheet.

“It begins in a whole different place. You want to know, for starters, what a young person’s work interests are, what their work values are, what do they want to get out of work?” Carnevale says. “You start with the person, and then from the person you want to know, OK, how do I build you an education and career pathway?”

HOPE: Satisfaction

Spring is planting season. For Spencer Risenmay, that means picking up truck-loads of potato seed, cutting it, and treating it with chemicals that protect potato plants as they grow. The earth must be tilled, then planters run across the fields.

“There’s a lot going on with planting spuds,” Spencer says.

As soon as the school day ends, he gets work on his family’s farm—6,000 acres near Idaho Falls—which grows potatoes, hay and hard red wheat. Spencer’s uncle runs the farm. His father and other uncles are managers at a corporate dairy farm.

Spencer hopes for a career in farming, too.

That’s not a guarantee, though. Trying to be practical, Spencer has considered other options, like joining the military, or using trades skills he’s picked up during his daily duties.

“Working on the farm has made me reasonably capable as a mechanic, and I know how to weld. So I could go into a couple of different fields there and get a few certifications and go to trade schools and be able to make a living that way,” he says. “In my more money-focused moments, I realize that being a farmer is not a very lucrative position, you know? And so I start looking at what people in other fields that I could do make. A good welder can be at six figures in the right position and if he’s good enough at his job.”

But no other work compares to how farming feels.

“There’s a lot of time, a lot of work, a lot of effort, but when when we get all the spuds in and we close the cellar doors—’cause every spud is in the cellar, every potato is in the cellar, the grain’s cut, everything’s done—the satisfaction I get, I’ve never felt in any other environment in my life,” he says. “And I don’t know that I would ever feel it anywhere else.”

Spencer studies accounting, personal finance and entrepreneurship at his high school, which offers business courses from the National Academy Foundation, a nonprofit that teaches workforce skills in schools. It’s preparation for what he aims to study in college: agribusiness, and the innovations shaping agriculture.

“I’ll drive a tractor, I’ll drive a truck, I fix stuff, but all I’m doing is labor,” he says. “I couldn’t tell you when potatoes are ready to harvest, you know, I just know how to run the harvester. A lot of that knowledge can come from working on the farm, but it’d take me 20 years to get there. A lot of it can come faster in a classroom, and I can get into some of the sciences.”

The college that interests Spencer most is Brigham Young University-Idaho. It’s a short drive from his home. He thinks its agriculture school is well-regarded and has a strong job-placement rate. It’s not too expensive—a priority for Spencer, who says he can’t afford out-of-state tuition. And it’s affiliated with his religious denomination, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“There’s the community aspect: I’d be almost completely around people that I share a faith with, and I would have a good college experience there,” he says.

Spencer won’t go to college right after graduating high school. He plans to complete a two-year mission for the church, in a location still unknown. That big commitment weighs on him, as does figuring out how to pay for college. He’s applying for as many scholarships as he can, “because every penny counts.”

But beyond the next six years, Spencer says he doesn’t worry about what may lie ahead. If he can provide for himself and his future family, and do his job well, he will feel successful.

“It’s not easy to find a stable job, a stable life,” he says, “but I would think if one was willing to work hard enough, they could get there.”

HOPE: Exploration

Efiotu Jagun has layers. She plays Ultimate Frisbee. She reviews grant proposals for the Durham Office on Youth. She picks up her little brother from school. She helps to lead a student-advocacy group. She watches Netflix.

“I hate being constrained,” Efiotu says. “I want to have the freedom to switch when I start getting frustrated or bored with something.”

She has felt pressure to just pick something and stick with it. When Efiotu started high school in an arts magnet program, she was expected to focus on piano and band. But it didn’t seem challenging enough. “I didn’t like the whole vibe,” she says. So she switched to a different high school with a dual-enrollment community college program.

When Efiotu maxed out on high school math classes by 10th grade, she moved on to advanced coursework. People praised her math skills. She prepared for a career in engineering—maybe mechanical, maybe aerospace. But she didn’t enjoy it.

“I thought math and science was my thing, but it was not,” she says. “I’m Nigerian, and I’ve grown up around a lot of other Nigerians, and they’re very STEM-y. Like everyone is in medicine or something—I grew up seeing that in my parents too, they’re very medicine-y—and I guess, like, I thought I had to do that, too.”

What clicked instead was an introductory sociology course.

“I enjoyed it so much,” she says. “And the stuff I learned in that class really stuck in my head.”

Still, when it came time for Efiotu to apply for college, she let engineering guide her. That’s how she ended up receiving a big scholarship from Georgia Tech.

Having never seen the campus, she chose to enroll—on her own terms. Instead of engineering, she plans to study public policy and sociology. Learning about liberal arts at a technology powerhouse isn’t the only way Efiotu might stand out at her college. She notes that the majority of Georgia Tech students are men, and nearly half are white.

“And I’m not white and male. So that might be a little … spicy, I guess,” she says.

That’s giving her pause. She wonders whether she would be happier at a historically Black university, like North Carolina A&T.

“They teach a lot of their classes from a Black perspective, which is missing from a lot of schools, and I’ve started to regret it,” she says. “I’m really wondering why I didn’t go there. I guess because of the expectation that Georgia Tech is a ‘better’ school.”

Success for me would be being my authentic self.

—Efiotu Jagun

Efiotu has other worries about college. That she could go into debt that she can’t pay off. That her grades might slip, and she’ll “crash and burn.” That she will “never find my crew of people—the people that understand me.”

Understanding Efiotu means embracing her layers.

“I want to learn a lot of new things. I want to be able to do a lot of research and just explore my interests academically,” she says. “And I want to meet a lot of new people from places or backgrounds that I haven’t been exposed to before.”

Thinking about her future reminds Efiotu of an honors project she worked on about Black women running for public office. It taught her about “respectability politics.” That’s the pressure some people face, she explains, to “change themselves to be more relatable to society, in order to be successful in their career.”

“I don’t want to end up losing myself trying to do what I want to do,” Efiotu says. “Success for me would be being my authentic self.”

II. ‘The passion piece is so important, as opposed to the paycheck piece’

When Brady Jones was a postdoctoral psychology researcher at Northwestern University, she worked with young people learning within what she calls a “highly competitive, pretty privileged culture.” Those college students often talked about the difference they planned to make as future leaders, Jones recalls: “‘What’s the startup I create that changes the world? How can I be this really impressive teacher who goes in and teaches disadvantaged students?’”

Jones now works as an assistant professor of psychology at the University of St. Francis in Joliet, Illinois. It’s a different kind of campus than Northwestern; a higher share of students receive federal Pell Grants intended for people from low-income families.

Yet St. Francis students also plan to change the world.

“They are so unselfish, balancing school with taking care of younger siblings, taking care of grandparents,” says Jones, who studies pro-social purpose in young people. “I feel like they are trying to fit their interests and career ambitions into this larger social circle they live in: Make a difference, and still help out my family and help this community I’m a part of.”

It’s a persistent trope that teenagers are self-centered. But consider social justice movements past and present. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, advocating for civil rights. The Sunrise Movement, pushing to address climate change. March for Our Lives, responding to gun violence. They’re all led by young people.

“Psychologists in past decades really thought about meaning and purpose being a midlife kind of thing,” Jones says. “Pro-social purpose and making a difference in the world is important to young people, too. Teenagers are particularly attuned to justice and fairness in the world. They are so flexible and creative. I think they’re better able to see the world as it could or should be.”

Teenagers are particularly attuned to justice and fairness in the world.

—Brady Jones

A pro-social proclivity is one of many traits that distinguish young people. They’re in a unique developmental stage—adolescence—that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine describes as “a remarkable transformation between puberty and the mid-20s that underpins amazing advances in learning and creativity.” Psychology research shows that adolescents are busy thinking about new activities and passions, defining their identities, exploring the world, establishing new social relationships and developing autonomy.

These tendencies have kicked in by the time teenagers are figuring out what to do after high school. Digging into what makes adolescents tick reveals a disconnect between what drives them and what adults tend to offer them.

Take that teenage desire to improve the world. It’s a strong sense of purpose that, as Jones has experienced, crosses socioeconomic lines. Andrea Moreno, the counselor in San Antonio, sees it show up especially in the students she works with who lack citizenship documentation. Applying to college is extra arduous for them, yet so many persevere, she says, precisely because they have a strong vision of the work they hope to do someday.

“They have a career in mind, and the motive behind that is their drive,” Moreno explains. “They are hopeful, and that’s why they do work so hard to get the 1,000 documents in.”

As young people seek pathways to vocation, some adults try to offer them little more than shortcuts to work. But that doesn’t appeal to adolescents, not even to those who really could use a paying gig. People ages 16 to 24 who are neither going to school nor working full time “prioritize pragmatism, but still want to feel passion for their job,” according to a study from the Aspen Institute of about 2,000 such individuals. Although they tend to care about job stability, the report says, “they also aren’t willing to pursue a program in a field that doesn’t interest them—even if workers in that field are in high demand.”

That’s similar to what leaders of the national nonprofit Advance CTE discovered when they tried to figure out what young people and their families want from career and technical education. The nonprofit identified 22 potential benefits of that kind of training, then asked more than 2,000 students and parents to pick the top three most important to them. The benefit that resonated the most was “preparing for the real world.” The second-most salient benefit? “Finding a career passion.” That ranked higher than “finding a well-paying job” and “earning college credit.”

“Policymakers talking about paychecks—far and away that is not what’s resonating with families,” says Katie Fitzgerald, former director of communications and membership of Advance CTE. “The passion piece is so important, as opposed to the paycheck piece.”

Of course, teenage passions can be fleeting. The fascination a young person feels about engineering on Monday may cool by Friday, replaced—for the moment—by an enthusiasm for poetry. Adolescence is a period of trial and error, of testing identities, pushing boundaries, grappling with pressures to fit in and stand out. Teenage brains embrace risk and savor reward, Jones says, making music sound better, drinking feel better, novelty more fun.

Risk-taking and exploration help young people mature and grow. And those who find themselves in college encounter opportunities for that behavior baked into the experience. Plenty of college students try classes out, make mistakes around campus, and move on, somewhat protected by a higher ed environment that encourages free inquiry and experimentation.

Rarely, however, does an adolescent who is not enrolled in college get the same opportunity to take risks—or the same forgiveness for failing.

So say the leaders of Baltimore’s Promise, a city-wide, “collective impact” effort to improve outcomes for Baltimore youth. One of its programs, called Grads2Careers, connects recent high school graduates with free job-training opportunities in industries including health care, information technology and construction. This helps to ensure young people don’t wander away from the workforce—but it doesn’t offer them much of a chance to experiment with career choices.

“We are asking young people to make a huge decision for themselves that more affluent young people can have four-plus years to figure out,” says Janelle Gendrano, chief operating officer for Baltimore’s Promise. “They are in this unfortunate position where they just don’t have the resources to be able to have the time and space to do that.”

As a participant-support coordinator for Grads2Careers, Greg Couturier recruits high school students and new graduates for job-training programs. Before signing young people up, he tries to understand and validate their interests—be it making music, working with their hands or helping other people. And Couturier seeks to reassure students and graduates that, if they encounter failure, that doesn’t have to define them forever.

“I think a lot of times people are too quick to say, ‘grow up and buck up and start making money,’” Couturier says. “I really just wish there was more of a space to kind of dream.”

I really just wish there was more of a space to kind of dream.

—Greg Couturier

Dreaming comes so naturally to most of us. The majority of humans—about 80 percent—have what researchers call an “optimism bias.” It’s a predilection for predicting positive outcomes regardless of the actual probability at play. This has nothing to do with one’s math skills. Instead, it seems to occur because most people are motivated to believe that achieving the result they desire is more possible than it actually is.

And which group has an especially high bias toward optimism? Teenagers.

“One reason in general people have an optimism bias is they tend to not take into account negative information that is in front of them,” says Tali Sharot, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at University College London. “Teenagers do this to quite a large extent.”

It’s like the old joke: Everyone thinks they’re above average. And when you’re young, there’s plenty of time left to prove it.

For example, more than 90 percent of respondents to a 2021 Washington Post-Ipsos poll of 1,349 teens from across the country believed it’s very or fairly likely they will achieve a good standard of living as an adult. Furthermore, 76 percent of Black teens and 68 percent of Asian teens said they will become rich.

Grown-ups could try to “financial literacy” those notions away. They could tell young people to be more realistic. To set their sights lower. To suppress their appetite for exploration and stifle the passion and hope that flood their brains.

Or adults could accept the boundless optimism of youth—as well as the challenge of clearing the barriers blocking some young people from their goals.

HOPE: Leadership

Princesa Ceballos tracks her schedule in a planner. For the high school junior who lives in California’s San Joaquin Valley, a typical weekday looks something like this:

Wake up by 6 a.m. Drive to school by 7 a.m., to trim bushes, clean rocks and dig holes for a group landscape project. From 8 a.m. to 9:30 a.m., practice showmanship with the goat she’s raising to sell. Drive home to take a test for school from 9:30 a.m. to 11 a.m. Until noon, prep for a tennis match. Drive back to school to feed the chickens and practice a script for an end-of-year banquet. Drive to the tennis courts for a doubles match at 3 p.m. From 4 p.m. to 6:30 p.m., have dinner with teammates. Head home, shower and do homework until 9 p.m.

Then, finally, until her bedtime at 11 p.m., Princesa rests—while looking at her phone.

“I am someone that really likes to get involved with extracurricular activities. I like to put myself out there,” Princesa says. “Although I am a little bit shy at times, I do want to make sure that I’m giving myself those opportunities to grow and expand as a leader.”

Princesa moved to the U.S. from Mexico when she was 3 or 4 years old. Her father works in the fields, picking oranges, lemons, grapefruits and mandarins.

“It’s very excruciating work,” Princesa says. “You get paid very little. And at the same time, you’re also working in very, very difficult conditions because you’re either working in extremely hot weather, where it’s 109 degrees, or you’re working in extremely cold weather, where it’s 30 degrees, and there’s very little precautions being taken.”

Her two older brothers work as teachers.

“They were both the first in our family to go to college, so they were a big inspiration,” Princesa says. “And I think that’s why I’m so inclined to go to college and feel like that’s something I want to do—because they were able to do it.”

She has her college picked out: California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo. She appreciates its small class sizes, its motto—“learn by doing”—and its campus near the beach. Her planned major: environmental science, with a minor in agricultural business. She even has her career selected: agronomist—a soil scientist.

“I want to be able to get my bachelor’s and my master’s and eventually my doctorate degree, even though it’s really expensive,” Princesa says. “Especially being a woman in, possibly, a STEM field, I think I want to be able to motivate others—once I do graduate—younger than me to pursue those types of careers.”

As a 17-year-old club leader and community-service volunteer and livestock farmer and science intern and athlete, there’s one activity that Princesa hasn’t figured out how to squeeze in, except for during those few moments before bed—rest.

“Some of the things that I really struggle with are my mental health, for the reason that it’s very difficult to balance so many different activities that I do,” she says. “I have all straight A’s right now, but it’s very hard to keep those grades.”

She also puzzles over how to thrive in the U.S. while staying connected to her Hispanic culture.

“Being able to love both parts and embrace both parts,” she says, “is something that I try to continue to work on.”

HOPE: Helping Others

Patients visiting a medical office usually spend most of their time with a nurse. That’s the person who greets them, comforts them and prepares them for treatment.

That’s the person Maytee Guadiana wants to be.

“They are people that help people a lot, and that’s one of my biggest dreams: to help others,” she says. “And not just my family—just help my community in general.”

Born in Mexico, the soft-spoken high school senior lives on the east side of San Antonio with her parents and, occasionally, her older brother. She remembers how, a few years ago, the family received a phone call inviting Maytee to participate in a dual-enrollment program, where she would supplement her high school classes with courses from a local community college.

“I was a little bit scared. I wasn’t really interested, but my parents, they were really pushing for it. They really wanted me to do this. My brother had done a similar program in the past, and they thought it was really a good option and provided really good benefits,” she says. “If I wasn’t able to, later on, afford to go into college, I would have at least something to lean back on.”

So Maytee signed up. She earned a certificate in computer engineering technology. But during junior year, she decided that computers are not really what interests her. She found a new direction by talking to her mother’s cousin, who works as a nurse.

“Everybody needs health care at some point. Everybody needs to have good health in order to live a good life,” Maytee says. “Nurses are a great part of this, and I just want to put my part in it as well.”

She plans to pursue that path at Texas A&M University at San Antonio, a college close to her home. She has always wanted to continue her education, she says, in part because she enjoys learning.

It also feels like unfinished business for her family. Maytee’s mother started college but then couldn’t afford to complete her degree.

“One of my biggest fears is that I end up like my mom,” Maytee says. “I just want to have the opportunity to finish.”

Her father, who works leveling houses, sought a job right after high school. Her brother, who works in roofing, did likewise.

“He had the opportunity, and he just didn’t take it,” Maytee says of college. “And I feel like I was offered the same opportunity, and I actually want to take it—because I feel like it’s an easier route, and it gives you more benefits than just going into the workforce.”

“I’m not saying it’s wrong not to go to college,” she stresses. “It’s just personally appealing to me.”

III. ‘There were so many barriers in the way’

Nahum Pacheco is the industry program manager for a Pathways in Technology Early College High School in Austin, Texas. It’s a public school that partners with IBM and Austin Community College to prepare students for careers by offering them the chance to earn an associate degree in computer programming or user-experience design along with a high school diploma. Most of its students are Hispanic and come from low-income families.

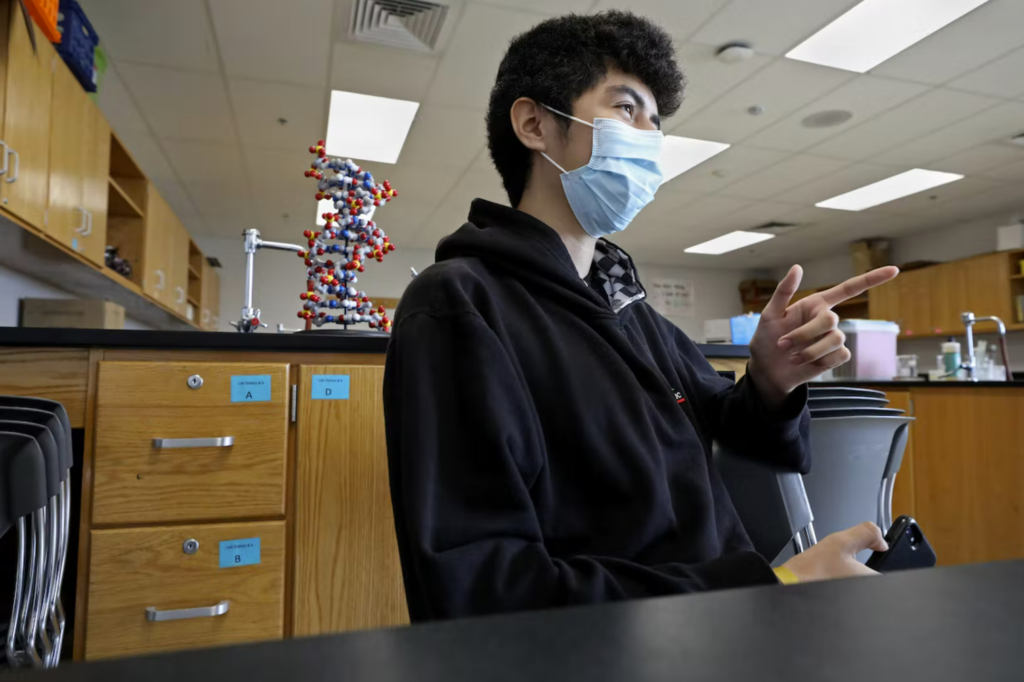

One day, the school hosted about 60 IBM employees for a mentorship event. Tech workers and teenagers gathered at long tables. Leaders handed out red, yellow and blue Post-it notes and asked students to use them to answer a question: What are your hopes and fears?

“The students went off on their fears. The adults could not believe it,” Pacheco says. “Kids were genuinely afraid for their food security, housing stability, legal status, immigration status, deportations.”

This is the reality for so many young people today. Hunger, violence and discrimination weigh heavy on the heart of a teenager trying to envision his future, let alone do his math homework.

These conditions trip up plenty of young people trying to leap into their futures. They’re stumbling blocks that can’t always be cleared away by youthful optimism and drive. Unease about this seeps into students’ conversations. They worry that they lack the grit, the motivation, the intelligence it seems to take to get to where they want to go.

These fears are reinforced when young people see their siblings, cousins and friends enroll in colleges that aren’t designed to support them—and stop out before finishing. That was the pattern at the New Orleans high school where Leah Lykins used to work. It was part of what prompted the former teacher and teacher coach to create an organization, called WhereWeGo, that aims to help young people and adults find job-training opportunities outside of bachelor’s degree programs.

“What students were doing after high school was actually going to college for a little while, experiencing extreme resistance in terms of unavailable support services and really difficult-to-navigate financial aid—like, some students were going downtown and doing their parents’ taxes at 17 years old,” Lykins says. “There were so many barriers in the way that the actual results were: It was more likely for a student to accumulate debt than to accumulate a degree.”

It was more likely for a student to accumulate debt than to accumulate a degree.

—Leah Lykins

Even though few young people are motivated solely by the promise of a paycheck, they’re plenty aware that money matters. They wonder how they’re going to come up with the dollars—sometimes more than they can imagine—to pay for courses and textbooks and bus fare.

For some students, the uncertainty is so great that college feels less like a smart investment and more like a foolish gamble. Other options seem like safer bets. According to research (not yet peer-reviewed) published in 2021 in the National Bureau of Economic Research, Black youth in Baltimore who have experienced “disruptive events”—like violence, eviction or a family member’s incarceration—tend to anticipate that they will face more adversity in the future, the kind likely to interrupt their education plans. This prompts many of them to enroll in shorter, more flexible postsecondary programs rather than seek a bachelor’s degree.

“It is a very rational decision for our students to choose not to go to college, just looking at the data of how many are going and how many are actually graduating,” says Rachel Pfeifer, executive director of college and career readiness for Baltimore City Public Schools.

The dissonance between the college-for-all promise and the barriers-for-many truth must be acknowledged. But adults who recognize that students grappling with hardship benefit from postsecondary options can slip all too easily into assuming that some pathways—namely, college—are simply beyond reach. That barriers to opportunity are immovable—maybe even acceptable—and so young people who need support to succeed in higher education should simply look elsewhere.

That teenagers afraid about their food security, housing stability or legal status must want cheaper, faster, easier ways to find jobs that are “good enough.”

But if you listen, you’ll hear that is not at all what young people are looking for.

Despite fears about failure and concerns about costs, many teenagers do still dream of graduating from college. The Washington Post-Ipsos poll found that 82 percent of respondents consider that important. That was true among 92 percent of Black teens, 92 percent of Asian teens, 88 percent of Hispanic teens, and 75 percent of white teens.

Why?

Perhaps they perceive that a bachelor’s degree conveys a long-term financial advantage. Students don’t need to understand economist Anthony Carnevale’s data to recognize that college is the postsecondary pathway of choice for the majority of wealthy families—who often go to great lengths to prepare their kids to compete for college admission.

“People are very aware—parents and young people of color—that we have a history of offering ‘not the best thing’ to Black and brown kids,” says Allison Gerber of the Casey Foundation. “They’re concerned that they are being offered something that is ‘less than.’”

Or maybe young people see college as a route to something else they care about. When a 2021 SkillUp Coalition and Charles Koch Foundation survey asked people ages 18 to 24 what they consider the most important result of education in one’s life, 30 percent said “to get a job or career,” and 70 percent gave a different answer. The top other results:

- to learn what one is good at and passionate about (21 percent)

- to become a better person in general (15 percent)

- to become a critical thinker (14 percent)

After all, few young people trying to find their way actually think, as Carnevale puts it, “in purely mercenary, economic terms.” Not even those with grumbling stomachs, or part-time jobs serving fast food, or their fingers crossed that one of their many scholarship applications actually pays off.

Just like their wealthier peers, students who may struggle to pay for college are driven by their hopes.

In Idaho, Spencer Risenmay hopes to continue his family’s legacy of farming. In Illinois, Freddy Zepeda hopes to build a career that makes his parents proud. In North Carolina, Efiotu Jagun hopes to learn and develop and live as her “authentic self.”

The false choice between personal growth or a decent paycheck isn’t serving young people well.

Across the country, teenagers share these aspirations. The Washington Post-Ipsos poll found that they value:

- having enough free time to do things you want to do (95 percent)

- being successful in a career (93 percent)

- having a family of your own (80 percent)

- making a difference in the world (76 percent)

- being involved in their community (67 percent)

Teenagers wading into the waves of adulthood don’t want to cling to life preservers. They want to navigate ships ready to sail as far beyond the horizon as they can imagine.

Many see college as the surest vessel for the journey. Not as an alternative to job training—they want that, too. They want it all. They want “the best thing,” as Gerber puts it. And why shouldn’t they?

Adults can divert their boats—or put wind in their sails.

The false choice between personal growth or a decent paycheck isn’t serving young people well. Their ambitions demand that adults reduce barriers to higher education in the long-term and create an array of other options in the short-term that speak deeply to young people’s values, genuinely serve their best interests and help them get to college eventually if that’s where they want to go.

“Why are these very binary choices in our country?” Gerber says. “If we thought less about these things as bifurcated, linear options, and more about multiple pathways to work and school, a four-year degree is never foreclosed to you.”

The work of redesigning entire pathways is daunting. But change doesn’t only happen at the level of systems.

It also takes place one conversation at a time.

FEAR: Making Mistakes

Robotic arms and computerized manufacturing mills are the high-tech tools students learn to use at the school Kaiasia Williams walks to in the morning, past palm trees and across train tracks. The center for advanced studies in Charleston, South Carolina, is the kind of place Kaiasia hopes will prepare her for her future.

She signed up for classes there after hearing about the center from a teacher who visited her high school. Even though Kaiasia appreciated her own school’s program for career and technology education, she worried that she wasn’t ready for the college where she hopes to enroll and the engineering field she wants to study.

“The students who apply to Clemson, they have years and years of experience,” she says. “I felt like I was lacking in some of the skills it takes to be a mechanical engineer.”

Be mindful that these kids are kind of trying to break a generational curse.

—Kaiasia Williams

Kaiasia aspires to that career because it combines “doing something I love, but making enough money to make sure that everybody else around me is good,” she explains.

She applied to Clemson because “I just had to look for my most-affordable option, but also the school had to have the qualifications that I wanted,” she says. “And I couldn’t go out of state because that would be too far for my mother to travel, especially with my little brother.”

This vision wasn’t always clear to Kaiasia, who will be the first person in her family to graduate from high school.

“It took a lot for me to get to the point of wanting to go to college because I just didn’t have the motivation to do it—because nobody around me did it before,” she says. “So I was all alone in my little track of figuring out how to submit college applications and the college essays.”

That makes it hard for Kaiasia to feel confident about her next step. In high school, she hears that “college is hard, it’s going to beat you down.” She plans to be hyper-focused at Clemson, but she still worries that she won’t stay as motivated as she is now. Or that her fear of failure will lead her to procrastinate. Or that she’ll end up being “my own worst enemy.”

“I feel like I’ll be fearful or hinder myself because I just can’t picture myself in these types of positions. I can’t picture myself going to college. I didn’t picture myself applying for college,” she says. “I can’t picture myself, you know, entering these classes—and I’m going to be doing this by myself.”

HOPE: Stability

When a visitor to a middle school in Austin, Texas, started talking about saving students money, it caught Alan Farfan’s attention. The eighth grader listened in as the guest described a special high school program—called P-TECH—that could help students get hired at a big technology company called IBM.

Alan didn’t know exactly what IBM was. But he liked the sound of landing a job at that kind of place.

So he signed up to attend one of Austin’s Pathways in Technology Early College High Schools. It sets students up to earn an associate degree in computer programming or user-experience design along with a high school diploma. And it connects them with people who work at IBM, an opportunity that Alan, who likes meeting new people, says he enjoys: “It was really cool talking to strangers that work there.”

As a 16-year-old sophomore, Alan says he doesn’t think about the future too much. “It kind of scares me, thinking about it,” he adds.

But he does know what he wants to do after high school.

“Hopefully get hired by IBM,” Alan says. “Software engineering—which is just coding—is basically a stable job, which can help me. And just having a stable job is really, really good, at least for me.”

IV. ‘It’s on us to open that window for them’

The high school student explained her plan: Go to college, then become a veterinarian.

“Tell me,” replied Rachel Pfeifer, the college and career leader for Baltimore City Public Schools, “is there anything you are doing to move you to that goal?”

The teen explained that to get to college faster, she hoped to graduate from high school in three years—instead of the standard four. To earn money in the meantime, she had a part-time job at a fast-food restaurant.

It didn’t sound like the best strategy, Pfeifer recalls: “She was not aware of what her competition in applying to some of these universities would look like with four years of coursework—not three—or what taking advanced classes would do for her academic profile.”

Yet the student was simply making decisions based on the best information that she had.

“She was actually really clear about her goal, but we had not provided her the structure and the guidance to get there,” Pfeifer says. “We are not helping our students understand how to plan, and then we are faulting them when, at the end, they aren’t able to implement or follow through.”

The aspiring veterinarian hadn’t needed a grown-up to give her a career idea, and she wasn’t looking for someone to talk her out of it, either. What she did need was for an educator who cared to check in on her progress. Make sure her class schedule set her up to succeed. Suggest she swap that fast-food gig for a part-time job more relevant to her goal of helping animals, like working at PetSmart.

It’s an approach to guiding teenagers that takes seriously both their grandest desires and their basic needs. Rather than lowering the ceiling of how high they dream, it raises the floor below them so that adolescents doing what they do best—learning, growing and taking risks—don’t have so far to fall.

This kind of mentoring takes time, knowledge and compassion. It can be tough for young people to come by in schools where counselors are responsible for hundreds of students at a time. And for this conversation to go over well—or even happen at all—the invitation to talk can’t come from a stranger who only summons you to an office for a few minutes each school year.

It has to come from a trusted source. When it comes to guiding teens, the messenger matters, experts say. And establishing a relationship, or better yet, tapping into a pre-existing relationship, is key.

When it comes to guiding teens, the messenger matters.

Even as young people exercise more autonomy, they remain invested in and influenced by the important people in their lives. Parents rank high on that list. In fact, most kids plan to take the path after high school that their parents prefer, and the majority of kids ultimately do (while others are waylaid by financial and other barriers), according to a nationally-representative Gallup survey of nearly 3,000 parents. Older siblings and cousins are big influences, too.

Students say they also seek advice from their teachers and school counselors. This gives educators the chance to clue students into options they might not hear about at home. That’s part of what Nahum Pacheco does at the P-TECH high school in Austin, Texas, where few students have family members who work in computer technology.

“Even for students interested in tech, it’s on us to open that window for them,” Pacheco says. “They have zero insight about what happens inside a tech company.”

A trusted educator may know just the right way to influence a teenager, perhaps by emphasizing particular financial or personal reasons to consider a higher education or job-training option.

“If you’ve already built the relationship with the student, you kind of know which one is going to work better,” says Andrea Moreno, the adviser for high school students. “If they already hate school and are stubborn and don’t have good grades, I’m not going to push something they don’t like. I’ll start with what you do like.”

But if Moreno contacts or tries to advise a student she doesn’t really know?

“They don’t text back,” she says. “They’re not interested.”

Similarly, students may shut out adults who seem more focused on pushing a particular message than on truly listening. That’s what Pfeifer realized was happening in Baltimore schools, where some students grew so tired of feeling pressured into applying to colleges they couldn’t afford or where their friends didn’t succeed that many simply avoided talking to teachers about their plans.

It’s a classic teenager attitude, Pfeifer says: “If that’s what you’re going to tell me and I don’t want to hear it, I don’t talk to you at all.”

And if students aren’t talking to trusted adults, they’re going to get information elsewhere. Many turn to websites and social media for guidance about their postsecondary options. Of course, those sources are of varying reliability. While some students say they search for high-quality data through resources like the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics jobs profiles, others turn to YouTube, where influencers promise to share secrets about hustling your way to success.

It’s difficult enough to find useful information about how people fare after enrolling in public or nonprofit colleges. It’s even harder to track down reliable data about the outcomes of many workforce training opportunities—let alone side gigs and investment schemes.

Filling that void for the young people of New Orleans is one of the big goals Leah Lykins, the former teacher, has for her platform, WhereWeGo. The website provides information about apprenticeships, certification courses and associate degrees available in real-time—similar to a list of cars that are for sale, right now. It’s published in a format intended “to feel like you’re shopping, being able to feel that there’s zero risk, like you’re just browsing,” Lykins says. “You’re just trying on all these different identities for fun, because that’s developmentally appropriate.”

The platform prominently displays key details about tuition costs and completion times for programs that lead to careers as a carpenter, or software developer, or paralegal. It does not emphasize what “category” these programs belong to, on the grounds that jargon like “hybrid college” doesn’t matter much to a teenager.

“The apprentice people, the community college people, the on-the-job training people—these are not different groups if you’re a person looking for a career. They’re the same thing. They are a way to get ahead,” Lykins says. “And so they need to be, from a user perspective, on the same page.”

Nor does the platform suggest that there is a hierarchy to the options it lists.

“We have to tap into the fact that young people are incredibly aspirational,” Lykins says. “The phrase ‘middle skills’ and ‘middle jobs’ is not getting anybody psyched. No one wants to be told that they’re going for the middle of the road, especially when there’s no reason why it is the middle of the road.”

No one wants to be told that they’re going for the middle of the road.

—Leah Lykins

If alternatives to college took teenagers’ aspirations more seriously, that might prompt young people to take a closer look at such options. Unlike, say, college mission slogans, few job-training programs explicitly market themselves by tapping into that teenage hunger to help others, says Oksana Vlasenko, vice president at Recruit4Business, which hires and manages employees for plumbing, electrical and security companies. But it’s not because workers in the skilled trades don’t make a difference, she adds. On the contrary: “They are what we need to survive in this world.”

For example, Vlasenko says, when Winter Storm Uri took out water and energy systems in Texas in 2021, who got the calls to help? “The plumbers and the electricians. It wasn’t the accountants.” And when the COVID-19 pandemic increased demand for UV lights and air-quality improvements, who came to the rescue? “Heating and cooling technicians.”

Billing a skilled trades apprenticeship as a low-cost way to land a high-demand career might not successfully sell the opportunity to a teenager. But stories about how technicians help their communities in times of great need? That might work.

“We should be advertising it as: Come make a difference and keep the world running,” Vlasenko says.

Of course, adding a gloss of fresh paint to a rickety bridge won’t help students cross it safely. If postsecondary pathways adapt and evolve to better appeal to young people, that could actually increase the need for caring, savvy adults to test that that new infrastructure is sound.

Experiments in change that are substantive, not just shiny, are underway. College leaders are starting to recognize that many people move through higher education in fits and starts, and so institutions are testing new ways to award incremental credentials that eventually add up to degrees, as well as creating bachelor’s degree pathways at community colleges and associate degree pathways at universities. Colleges are also trying new strategies for reducing students’ costs and supporting their basic needs. At the same time, companies are investing in paid apprenticeship programs for fields outside of the skilled trades, such as software engineering and digital marketing. And leaders are figuring out how to combine college and job training in ways that improve both, like offering college credit for apprenticeships and encouraging more students to earn credit from community college courses while still in high school.

But in Baltimore, educators aren’t waiting around for employers, policymakers and higher ed leaders to fill old potholes and pave new roads for students. Young people there need better guidance today about where to go tomorrow.

Some students aspire to work in restaurants or hair salons. Pfeifer knows those jobs rarely pay enough to support a family. Other students dream of going to college. Pfeifer knows many teens can’t cover a $13,000 gap in financial aid.

She wants the best for each of them. She respects what they think is best for themselves.

“It’s fundamentally a dignity thing. A human flourishing kind of thing,” Pfeifer says. “Our students live in a world that is unfair. And in many cases—not all the time—they fall on the short end of the stick in that unfairness. I’m not going to be the one who doubles down on that by making everything for them a matter of practicality and not a matter of being able to dream and contribute their whole selves to the problems and the challenges we face in this world.”

Still, Pfeifer can nudge students toward the good lives they desire.

Under her leadership, educators in Baltimore rethought their career-readiness programs. They identified professions that pay workers enough to live on. Then they prioritized teaching students about the pathways that lead to those jobs.

In this new curriculum, “the living wage became the floor,” Pfeifer says—a precondition for each conversation, a guardrail intended to deter students from straying into options that might exploit them.

“I can make the adult decision—the system’s decision—to take that off the table for a young person,” Pfeifer says, “and give them the space to do the dreaming without the worry about the dollars and cents.”

It’s not that young people aren’t good enough for some pathways. It’s that some pathways aren’t good enough for young people.

It’s a lesson today’s teenagers can teach adults—if they’re willing to listen.

HOPE: Aiming Higher

When he thinks about college, Freddy Zepeda looks forward to more independence. But his other higher ed goals tie him closely to his family.

He plans to study bioengineering at the University of Illinois Chicago, several miles north of where he lives with his mom and two sisters on the city’s South Side. It’s a major he selected in part because he enjoyed taking science classes while dually enrolled at a public STEM academy and a local community college.

Freddy’s relatives also influenced his choice.

“In eighth grade, they were talking to me about what I wanted to pursue when I got older, and I would look up to my cousins and be like, well, most of my cousins are doing engineering and are in STEM, and I want to take part in it as well,” Freddy says. “And also my father was a big figure as well. He would tell me, ‘oh, engineering is a good career,’ you know?”

Getting a good career in a field that he likes is Freddy’s main motivator for seeking a bachelor’s degree. He will leave high school with an associate degree in web development, and he considered sticking with community college after graduation. It’s the path his older sister is taking to become a nurse—one that she tells him is more affordable than other options.

But Freddy talked to cousins his same age, and they decided to pursue the four-year experience.

Freddy understands that may be expensive. To help pay for tuition and books, he plans to find a job that fits with his college class schedule, and to work during the summers. If bioengineering doesn’t pan out for him, he’s got a back-up plan: studying art. He’s enjoyed learning about photography and pop art through an after-school program that pays him to participate.

He knows his family wants him to thrive, and to gain access to employment that’s different from their own. His mother works as “a cleaning lady,” he says, while his sister works in a restaurant.

“They would tell me that they wouldn’t want me to work in those types of jobs because, well, my parents come from Mexico, and they came here to give me a better life. And so I think they expect a lot from me,” he says. “They will definitely not want me to work in a job related to theirs, and want me to aim higher.”

But no matter what college major or career Freddy ends up with, he knows that he will be successful.

“I’m very positive,” Freddy says. “And I won’t give up my dream.” ⚡